Epistemology Wars

Seven books I've read in the last two months and the common, culturally-relevant thesis that joins all of them together.

The Question

I've been reading half-a-dozen books over the past two months, and in the back of my mind I keep circling around a question that I need an answer to. It's buggin' me.

Are some civilizations and cultures better than others? If so, why? It's a very tricky question.

There are three main schools of thought. The first is that better civilizations flourish over poorer civilizations. This seems like the naive and standard thing an observer would believe. The second is that civilizations, instead of getting better or worse, simply cycle through various phases or flavors through the centuries. Life is but an endless cycle. This is what many of the ancients felt. Finally, there's the belief that there are no criteria for ultimately judging such a question; every civilization has as much as good as any other ... or as much bad. The question itself is meaningless. Many folks call this something like "moral equivalence" and it feels like giving up the field of discussion in despair before a discussion even happens. It's the also most commonly-felt attitude among scholars who study various civilizations and cultures throughout time, although this attitude is a fairly recent development.

The best way to go at this is, oddly enough, to define "best". If you take a random person from any point in history or from any culture and drop them into another culture, are there things a culture could have that most people would find better or worse?

While you might be able to make a case that some deeply religious people in various cultures would refuse to acknowledge any good in other cultures, to me it seems obvious that this is stretching the imagination a bit too much. Would you rather live to 80 or 30? Would you like to be able to travel hundreds of miles instantly, talk to people all over the world whenever you like? Do you want to understand how nature works, would you like to control energy and riches never even dreamed of by ancients even as the poorest person in society? Would you like to be assured of food, know that you have shelter and medicine available close-by?

We can pick and choose which of these we might like or hate. We can make arguments about whether all of these things are available equally to everyone in any one culture or society. What we can't do, at least not with intellectual honesty, is claim that in general, these attributes (and attributes like them) don't make any one culture better than another. Mankind would disagree.

We have defined "better" or "worse". It's mostly this bag of attributes. Notice that none of these relate to religion, skin color, gender, sexuality, where you're from, or anything else that can easily lump humans into one bucket or the other. Better or worse, from our standpoint, are words that any human could observe and relationships that most all of us would agree on. It's also not about politics or morality. There's a difference between saying these things just exist commonly among the population and saying people are guaranteed these things. We're not talking about what people believe or think, simply what they can observe, what they commonly know and agree that they know regardless of any simple external label we might stick on them.

The Thesis: Epistemology Wars

And therein, I believe lies our answer. The quality of a culture is directly related to how we know things. The science and philosophy of how we know things is called "epistemology". It covers everything from religion to science, rumor to storytelling. How do we know? How do we know the world is round, or that there are other planets around other stars? How do we know that not stealing or killing leads to a better lifestyle than being a criminal? How do we know that Luke did the right thing by leaving Tatoonine? How do we know that getting a college education beats never learning to read or write?

Most of us know all of these things and much more, yet the huge majority of things we know we neither experience or can prove mathematically. Somebody tells us something, perhaps somebody we respect. We read about something. We hear people online or in the grocery store talking about things.

We use the word "know" much like we use the words "better" and "worse", in a very loose way. There are people who say they know all of these sorts of things because they came to them in a vision. There are people who say it's impossible to really know anything. Oddly, this word also breaks down along the same three lines of thought: over time we constantly know more and more important things, over time people cycle between knowing various kinds of things, and there is nothing that we can know that is universally true; it's all relative.

My thesis: the way the average person commonly knows something in any society leads that society to over time be better or worse (based on our universal markers)

The Supporting Argument

There are various general type of cultures based on the commonly-used epistemology in-place among their people.

It is true because I told you. I am your tribal leader, your prince, your parent, your priest, your shaman. I will tell you anything that's worth knowing and I will tell you what you should know about it. Your job is simply to consume: eat, talk, reproduce, shop, chat, and otherwise be part of the herd of humanity I am responsible for managing. I have no ill feelings towards you; in fact, I may love and cherish you dearly. You can't know everything, so I and my friends who are important will figure out what's important and what the truth is. We'll let you know when you need to know it. Don't sweat the details.

The government is the knowledge. Not only is this knowing stuff so important that we've got you covered, it's so important and things have gotten so complex that we've organized ourselves into societies where the government is the knowledge. The king is a deity. The Greeks figured everything out centuries ago. The church fathers know what they know, the church fathers know how to read and write. They'll handle knowledge, science (although there was no word for that), and our relationship to the king, the saints, and all other forms of higher deities in our lives. Did your crop fail? The local chieftain and his shaman not only knows why, they might make it fail again if you don't pony up with a good sacrifice this spring. We worship Caesar among many other gods because he is a god, just like the rest of them.

There is nothing worth knowing that we can truly share with one another, just the work. Monks of various religions have felt this way throughout time. Many tribal groups incorporate it to some degree. Is there a Great Spirit, a One God, a universe that we can become part of? Yes, but there is no rigorously-describable definition or form. There is a greater mysterious nature of things. It is something each of us experiences inside of ourselves. It really doesn't make sense to share these kinds of things in a firm governmental structure. God(s) are everywhere. God(s) are nowhere. Perhaps the Sky God made the rains stay away this year, perhaps she brought a plague upon the land. Perhaps one of the gods made another god angry. This is something each of us is required to look inward to fix. We make sacrifices. We perform public acts of contrition. We walk from town-to-town beating ourselves with sticks. It is an inward-focused, yet oddly performative epistemology. As the Buddhist monks say, "Before enlightenment, I get wood, make fire, get water, make breakfast. ... After enlightenment, I get wood, make fire, get water, make breakfast" (Becoming one with everything is such a powerful experience that we show our change by nothing changing. Before that we are obviously flailing around trying to become enlightened) God is everywhere and nowhere.

The things of the gods are not the things of practical, day-to-day work. There is a difference in definitions. "Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's" Jesus said. The things you believe about some things, like what kind of weather we're having or what happens after you die, are not like the things you commonly interact with, like building houses, paying taxes, or working a job. There are domains of knowledge. What these domain are might be left completely undefined; simply knowing there are two different kinds of things to know, the spiritual/mysterious and the obvious/reasonable is enough to form a different kind of society. There's a line.

The Monkey Wrench

All societies, of course, have a little of each of these. People are not uniform robots, Most societies, however, are built around a general way of thinking that falls into one of these camps. This has consequences.

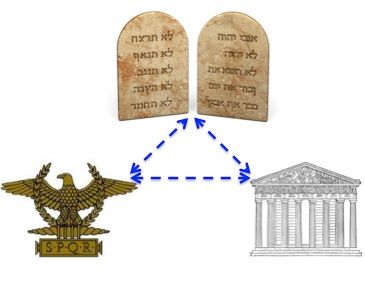

Monotheism, however, throws a monkey wrench into all of these forms of epistemology. Combining monotheism and writing (by that I mean writing among the common people about normal everyday things such that people in the future can read them)? That blows everything up.

Monotheism insists that there is one, single god, no matter what that god might be. That means that there must be one source to all of the answers to all of the questions we might be having. "God does not roll dice with the universe" said Einstein. Do the people far away speak a strange tongue and act weirdly? In the polytheistic past people believed that everybody had their own god, so who cared? But now that there's only one god, why would god make things to be this way? People started to insist that whatever your beliefs about how you get to understand things (your "epistemological framework", if you like big words), has to make sense for everything, not just you or your tribe. Even if you believe there's no god at all, that's a universal statement. Monotheism over time forces epistemology to be universal.

Many belief systems have tons of deities. These systems don't become better (based on our earlier definition) over time because there's no reason to. There are so many definitions of everything and why things work that there's no universal ground to stand on to build a modern society. It is a happy life, but it is a life that will be mostly the same for thousands of years.

Likewise, writing really screws things up. Now, not only do we have to come up with one answer for how we know stuff, that answer has to make sense over multiple generations. We've never had to do that before and it's a terribly difficult thing to do. It seems that there are some things that we can reason about over the centuries. These things should be useful in the future. There are other things that we'll never agree on, either today or anytime in the foreseeable future. It's really, really tough sorting those two epistemological categories out, much less coming up with a system for reasoning using them.

Why The Fall Of Rome Was a Wonderfully Horrible Thing

Up until Rome, most of humanity lived in a polytheistic community culture that was performative in nature. We did things, public things, to show that we knew the important things we were supposed to know and followed the rules of our society, whatever that was. In that world, the Greeks had started to use the dialectic to bring together various cultures to come up with universal ways of categorizing things, and the Jews had started down the path of monotheism. These things had happened in many other places over the centuries. So far, nothing was terribly unusual, aside from all of that writing going on (and surviving), perhaps.

Rome changed that, partly because early Rome was a universal idea: you were a Roman citizen or you were not, and these things had important implications in your life. Once again, Rome was not unique here, but there were not that many civilizations that controlled such vast empires from one person. At first the things Rome controlled, like in all other empires up to that point, were practical things like where to pay taxes, worship, or send your children into battle.

The Caesars, like many universal rulers before them, started declaring themselves gods, or at least god-like. This made the empire and its expansion even more robust. Being a Roman was not just a civil or practical matter; it meant that you fit into an entire way of believing in things and understanding things that hundreds of other cultures also fit into. It was a mix. Everybody believed whatever they wanted, yet there were some things, very clearly-defined things, where there was no room for doubt or variation. The government was responsible for how people came to know stuff, but there was a line. This also had happened before with any great empire, but I believe Rome managed to have the most variation while keeping things under one roof. Things were good for the Romans.

Until disaster happened.

Enter into this picture of expansion and conquest two ideas. The Greeks brought the idea that we could reason about anything we wanted and come up with the "truth" for that area that then other people, when properly educated, would also respect and use. They showed this over and over again with things like inventing biology, natural science, and so forth. Greeks seemed a little "fluffy" to the Romans at first. The Greeks slept on beds, for goodness sakes! They taught "philosophy" to their kids! If they would have been any good at fighting, the Romans wouldn't have conquered them. Yet, then again, the ideas they're working out are timeless and quite useful. They're creating a pattern of interaction where people of all sorts of cultures can come together and by interacting learn things and do things they never could before.

Freaking Greeks.

The second idea was also an old one in new clothes. The Jews had this idea of a single god and culture that was almost impossible to stomp out. In fact the Romans burned their entire capital to the ground and wreaked major destruction on them, in more than one instance, yet still they clung to this idea. Finally, as the pressure mounted, they came up with this new thing, Christianity. There was one god, but he handled the heavenly things. Christians could participate in the rest of society, yet (secretly) they had all sorts of other odd things they believed in, like eating the flesh of their founder. Their founder died and they talked about love and self-sacrifice. How can you use force to squish a religion where the more force you use the more people believe in it?

You can't. Over three centuries Rome eventually lost to this new religion. With Constantine it became part of the universal religion that was Rome. While it was a practical and logical decision at the time, nobody really could figure out how it was all going to work.

Freaking Christians.

Rome Fell and Modern Civilization Rose

Christianity was a monotheistic religion. That meant only one god and one way of reasoning/learning about things. People asked: what was that way? (One bishop in the 4th century complained that he couldn't go outside and do anything, including buying a loaf of bread, without getting into a theological discussion with the merchants and other random people on the street) Nobody knew, since up until that point it had been scattered all over the known world. Caesar was part god, right? Does that did that mean he was still part god? Perhaps he was a priest? Nobody knew. There was nobody to tell them. But each person knew that they had to start figuring it out. This change presented a very different situation than mankind had experienced before.

Three of our four forms of epistemologically-typed civilizations and cultures were all thrown into the mix and were all equally important: "It's true because I told you", "The government is the knowledge", and "The things of the gods are not the things of practical, day-to-day work" All three of these had to be equally applied for a large-scale government to work. The fourth, where there's nothing to universally-know and we are one with everything, was fine for the average citizen (mostly), but couldn't form the basis of any sort of large social structure that fit in with the other three.

What happened over the next fifteen centuries or so was that society, people, government, knowledge, and culture fought wars back-and-forth about how to balance all of that. In the year-to-year fight, it was a battle over control, but in the decade-to-decade and century-to-century viewpoint, it was a battle over how we know things. It was the Epistemology Wars. It led to many things, including The Enlightenment, which was premised on the idea that it was up to each of us to work out these answers on our own. Government was there so that all of us, with all of the various ways of living we have and ways of knowing, could freely talk and work with each other, coming up with more and more useful ways of understanding and learning that future generations could use.

Each of us are free to decide individually how we come to know things. The purpose of any structure, whether government or organizational, is to provide the minimum amount of rules necessary for all of us to freely talk about our methods of learning and what we've discovered so that all of us can learn and improve together. It's not about the details of what we're learning or whether something is true or false. It's about the open and unrestricted sharing of various systems of knowing things.

Modern civilization has been a story about battling each other about how we know things. The compromise that the Western Intellectual Tradition has come up with is the best answer we have so far. It's what has demonstrably made many civilizations and cultures better than others, even non-western ones. As far as we know, it's the only and best tool we have going forward to make future generations, societies, and cultures even better than the ones we have today.

You're welcome to come up with something else, after all, improving the species is the entire idea here, it's the goal, just don't repeat the same mistakes. We don't want to be those people who keep repeating the same mistakes over and over again while expecting different results.

###

* There's a ton of room here for nitpicking, of course. Any one of these topics represent a possible future of lifetime study. Many, because of the need to shorten the discussion, have been purposefully simplified to the point of being arguably misrepresentative. Cultural relativism, the role of various religions in promoting or repressing science, and the infinite mixture of all of these forms of epistemological reasoning in any culture are probably the top areas that bother me. There's a lot of discussion around Kuhn, Hegel, and Adam Smith/J.S. Mills that are immediately relevant. There's a recurring pattern in most of these subjects about things that have become fodder for the culture wars not actually being in conflict when viewed at enough detail. Having said that, there's just nothing to be done. Links are provided for those wanting to dive down further. I'll cover deciding what amount of detail to use and how to sort out real from imagined conflict when I cover pivot questions in a future essay.

Comments ()